These introductory remarks will use the work of Ahmadou Kourouma as a starting point to help cast light on the notion of “African Humanities”, on their place in world culture, and on their role in higher education today and in the future. In particular, Kourouma’s perspective of decolonization and his reimagining of French language operates a “de-centering” (to use a notion developed by Souleymane Bachir Diagne) that displaces and reinvents the experience of the universal as it has been offered by European culture. Such a de-centering can provide a template for the expansion of African Humanities in higher education.

Conferences 2024

Workshop “‘The African Humanities Project”

December 16-17, 2024

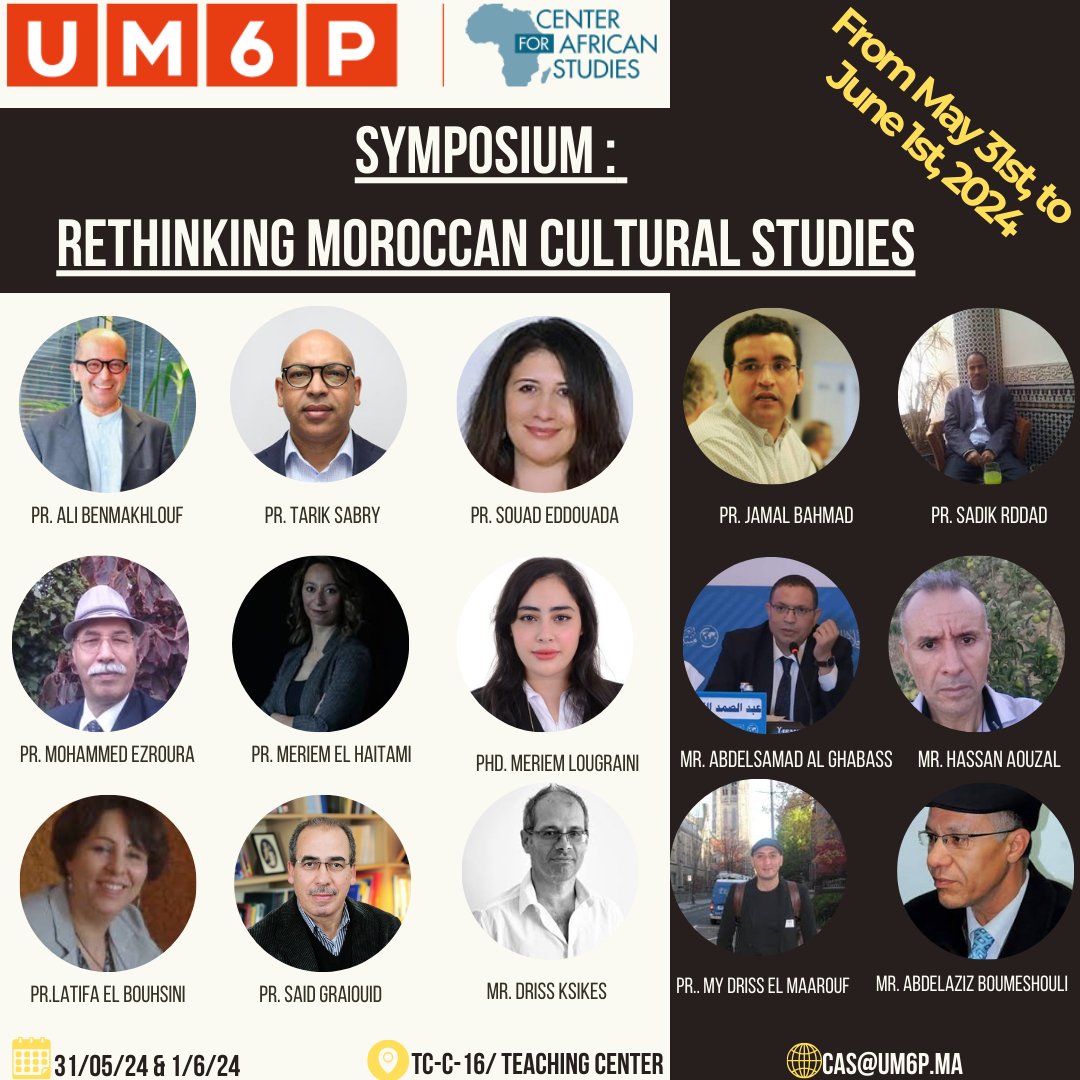

Symposium “‘Rethinking Moroccan Cultural Studies”

May 31- June 1, 2024

Symposium “Actualité’ of African Philosophy”

January 15-18, 2024

I- Workshop “The African Humanities Project”

December 16 – 17, 2024

UM6P Video Rewind : The African Humanities Project Workshop

A Home for African Humanities

By Wendell Marsh

“Enchanting” is the most appropriate word to describe the African Humanities Project

Workshop held December 16 – 17, 2024 at the Center of African Studies of Mohammed VI

Polytechnic University – Ben Guerir.

December 16, 2024

Abstracts

This is the story of a black woman migrant from the Tafilelt region in the Southeast of Morocco to the Northern city of Fes at the end of the 1930s. Tafileft was both the first and last bastion of resistance to the French armed intervention in Morocco and by the mid of the 1930s, most parts of this region were falling to the stronghold of the French artillery. Consequently, an unprecedented movement of outmigration took place, when a dispossessed population headed North, notably to the city of Fes. I reconstitute part of the life trajectory of migration of Khnata Bint el Bukhari, from Tafilelt to Fes, by recalling fragments of herstory, as patched for me by family members, and friends, and by how memory re-arranged and re-organized them. I use this story as an entry point to speak about the varied meanings of blackness in Morocco under the French protectorate, and the symbolic spaces that blackness enabled and forged in millennial bourgeois cities like Fes. Khnata’s story illustrates a gendered organization of space, and labor, but also women’s trans-racial solidarities, and the social mediations that the racial fabric of the city enabled in colonial Morocco.

The earliest written reference of Wangārī besides what we learn from the Mandinka oral traditions is that by Abu ‘Ubayd Abd Allah al-Bakrī of Cordoba (Spain), who, in 1068 A.D., wrote about a West African city, Yarasna, inhabited by a community of Muslims that he called “Banu Naghmarata,” –viz., “Banu Wanghmarata,” the tribe of the Wangāra–. He adds, “They are Blacks, traded in gold, and spoke a’jam–i.e., a’jamia, a transliteration of the Mandekan language using Arabic scripts–. Yarasna symbolized the 11th-century development of the Bure goldfields over the old famous ones in Bambuxu. Medieval Arab travelers might be equally familiar with Fulani or Takrūrī and the toponym and ethnonym that derived from it–viz., Takrūr and Tekayrne described it as a territory extending beyond the Senegal River to reach Kanem and Bornu. Takrūrī and Wangārī traveled to conduct trade, teach, and preach Islam. This paper is drawn from an ongoing book project, al-Safar: The Religious Art of Hiking. It explores the story of mobility between the 14th and 17th centuries within the shared cultural and geographic unity of West and North Africa. This mobility was shaped into a theoretical, cultural, and spiritual framework that established a code of conduct for the Takrūrī and Wangārī communities of West Africa. Mobility, or the “art of hiking”—the practice of traveling—developed its guiding principles as conceived by the 13th-century Mandinka scholar al-Haj Salim Suwari. Drawing from these principles, The Art of Hiking recounts what I term soft jihad—a shift from jihad as enacted by al-Majili, toward fostering ethnic fluidity and expansion beyond the dar al-Islam through preaching, trade, and teaching. The art of hiking also encompasses the diplomatic skills developed by the Wangārā and Takrūrī communities, enabling them to serve as courtly intermediaries, representatives, and secretaries in managing embassies and correspondences. Their involvement in politics, diplomacy, and state-building, combined with their mastery of mobility and literacy, gave rise to a sophisticated system for gathering and circulating information. Over centuries, this system produced advanced geographic and cartographic knowledge. This paper explores the roadmaps that were created and passed down through generations as written documents. These roadmaps guided the Wangārā and Takrūrī as they connected—through their journeys—the regions along the Senegal River to Morocco, Egypt, Mecca, Medina, Damascus, Sinai, Haifa, Acre, and Jerusalem.

Over many years of ethnographic and historical research in southeastern Morocco, I have observed how local families use historical objects and household artifacts to narrate their local family histories. Items like Qur’anic tablets, date-storage pots, and slave emancipation documents serve as storytelling vessels, amplifying the voices of Haratine and other marginalized groups. These narratives challenge elite-centric written accounts by centering material culture as an archive of subaltern voices and emphasizing the agency of objects in mediating memory and identity. Inspired by Daniel Miller, Arjun Appadurai, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, I underscore how these artifacts intertwine with the sensory realities of Haratine communities, reshaping our understanding of history and identity through the material and embodied dimensions of marginalized lives.

In this talk, I follow the trajectory of a nineteenth century West African traveler. In 1835, Abū Bakr al-Ṣiddīq Waṭara, a Timbuktu-born man who had been enslaved in Jamaica for thirty years, undertook a trans-Atlantic and trans-Saharan journey, in a bid to return home. I explore the role and meaning of distance, diaspora and dislocation in Watara’s understanding of himself and of the world, by centering his family ties and upbringing in the Western Sahel.

The purpose of this paper is theoretical, normative, and historical. The aim is to explain and recommend a conception of the humanities – understood less a set of academic disciplines than as education in and through culture. This conception is objectivist in the sense that it is based on the idea that education is a process through which we not only acquire skills, but also become more sensitive to the qualities of the objects studied. The value of an education depends not only on its social utility, but also on the quality of the objects studied. This objectivist conception is borrowed from aesthetic theory, especially from a certain understanding of the judgment of taste.

The debate on the judgment of taste, from which this objectivist conception is derived, took place particularly in Anglo-Scottish philosophy in the second half of the eighteenth century. It opposed Alexander Gerard to David Hume on questions that are essential to any reflection on the humanities in the plurality of cultures: Are common sense and anything resembling common or universal reason not tainted by Eurocentrism? Should not good taste, and more generally the progress of education and the refinement of culture, be understood as the development of a sensitivity to the qualities of objects – especially the products of art and technique, but also natural objects – itself based on the exercise of all the powers of the human mind? Is Eurocentrism not blind to the variety of objects that deserve to be appreciated and placed at the center of the humanities?

The aim is to show that the objectivist approach to the humanities has good arguments against a universalist approach. The latter relies primarily on features common to all human beings, especially their capacity for discussion and coordination; the former is compatible with reasonable relativism and relies only secondarily on these common features. It assumes that the humanities consist in the exploration of objects that deserve to be discovered and frequented. Thus, the first question a conception of the humanities should ask is not what we have in common as human beings, but what we value as human achievement from a particular culture.

African universities have arrived at a fork in the road. One path leads through the land of decolonization towards epistemic autonomy, the freedom to think through one’s own conditions through categories that correspond to those conditions. The other path passes through disruption, a transformation of the academic landscape in Africa through market-oriented education providers. How might the humanities in Africa be thought at such a juncture? Reflecting on a lecture I gave on Shaykh Musa Kamara (1864-1945) in Saint-Louis, Senegal in the summer following the most recent presidential elections, I describe the present terrain and insights that the life and works of the colonial-era Muslim scholar offer for our times. Kamara wrote a monumental history of West Africa at a moment when colonial discourses represented Africa as a continent without writing or history. His dream of an Arabic-French edition of the work has yet to be realized. And yet, his body of work and his many returns present a parable about the fate of the humanities after colonial domination.

This paper will examine Moroccan arts and cultural diplomacy in light of Morocco’s return to “Africa” and shift towards the South Atlantic. In 2017, Morocco returned to the African Union, and Morocco and Cuba re-established diplomatic relations (broken since 1980). Morocco’s Latin American/South Atlantic policy is an extension of the African policy, deploying a discourse of “Afro-convivencia,” depicting the kingdom as source and conveyer of Andalusian tolerance and African culture, a reversal of the Black Legend.

December 17, 2024

Abstracts

Afrique blanche, Afrique du Nord, Maghreb, Grand Maghreb, Berbérie… sont des noms donnés à la partie nord-ouest du continent africain pour le séparer de ce qu’on a appelé « l’Afrique noire », « l’Afrique subsaharienne ». , « bilâd Soudan », « bilâd Zanj » et Takrur….Certains de ces noms remontent au Moyen Âge avec le début des relations entre les deux rives du Sahara et l’essor du commerce caravanier, et d’autres remontent à l’époque coloniale, inventés par les Européens. Ce qui est commun entre dénominations, c’est qu’ils font du Sahara une frontière environnementale et naturelle séparant ce qu’on appelait « l’Afrique blanche » et « l’Afrique noire », consacrant ainsi l’idée de deux continents en un seul, et des frontières qui transcendaient les frontières géographiques pour ancrer dans l’imaginaire des Africains eux-mêmes une distinction « raciale », à tel point que les citoyens des pays du Maghreb ne se considèrent pas comme africains, leur imaginaire collectif exclut la dimension africaine de leur appartenance et de leur identité. Nous retraçons le processus historiques et idéologiques de cette séparation entre « Afrique blanche » et « Afrique noire », tout en réfutant la thèse selon laquelle le désert du Sahara constitue une frontière naturelle et un espace impénétrable séparant deux mondes différents. Nous montrons comment les études sahariennes et africaines des dernières décennies ont dépassé l’idée du Sahara comme frontière pour un approche qui conçoit le Sahara comme espace dynamique de connectivité et d’interdépendance sur la plan interne et avec son environnement régional et mondial

On posera d’abord la question de la manière dont s’est constitué l’idéal d’une Afrique globale, d’une Afrique comme totalité. On retracera ainsi l’histoire du panafricanisme. On s’interrogera ensuite sur les formes que prend, aujourd’hui, cet idéal et sur la manière dont les humanités africaines peuvent et doivent contribuer à sa réalisation et au développement de la présence africaine dans le monde.

This paper explores African antiquities as a foundation for developing an “African humanities,” examining how African and African American scholars have historically engaged with ancient Egypt to assert Africa’s central role in universal history and the humanities. By revisiting Egypt, they challenge prevailing narratives that have long excluded Africa as a significant agent in the history of civilization. Spanning from the late 1800s through early nationalist movements, this study investigates why the antiquity debate remains essential to framing Africa as an origin of historical and cultural knowledge and highlights the critical perspectives and circulatory frameworks that seek to reimagine Africa’s place in the humanities.

African humanities and social sciences, funding pools, and how to mobilize existing capacities across African universities

This presentation provides an overview of the current state of African humanities, highlighting key tensions between social science and humanities approaches and outlining recent academic offerings in both the United States and Africa. It examines the development and teaching of the undergraduate course African Civilization at Columbia University and reviews recent anthologies and syllabi to map emerging frameworks in African humanities. The presentation addresses the distinctive pedagogical challenges and opportunities in this field, particularly the dynamic interplay between theory and practice in designing a curriculum that is both inclusive and globally relevant. Additionally, it considers how these tensions shape course design, student engagement, and the broader mission of advancing African humanities curriculum development at the high school and college levels.

This talk explores the imperative of decolonising the curriculum, emphasizing the integration of subaltern voices—feminist, southern, postcolonial, and ‘other’—within academic institutions. By recontextualizing traditional Eurocentric narratives as vernacular expressions of northern academia, we challenge the universality of northern theory and engage with southern knowledge to dismantle hegemonic structures. Specifically focusing on urban geography, we confront the discipline’s ‘unbearable whiteness’ and embrace the transformative potential of the ‘undercommons,’ which includes black, indigenous, poor, feminist, and subaltern voices. This talk will interrogate who gets to represent the ‘global south’ in historically Eurocentric disciplines, aiming to elevate subversive intellectual work and contribute to a more pluralistic understanding of the ‘global south.’

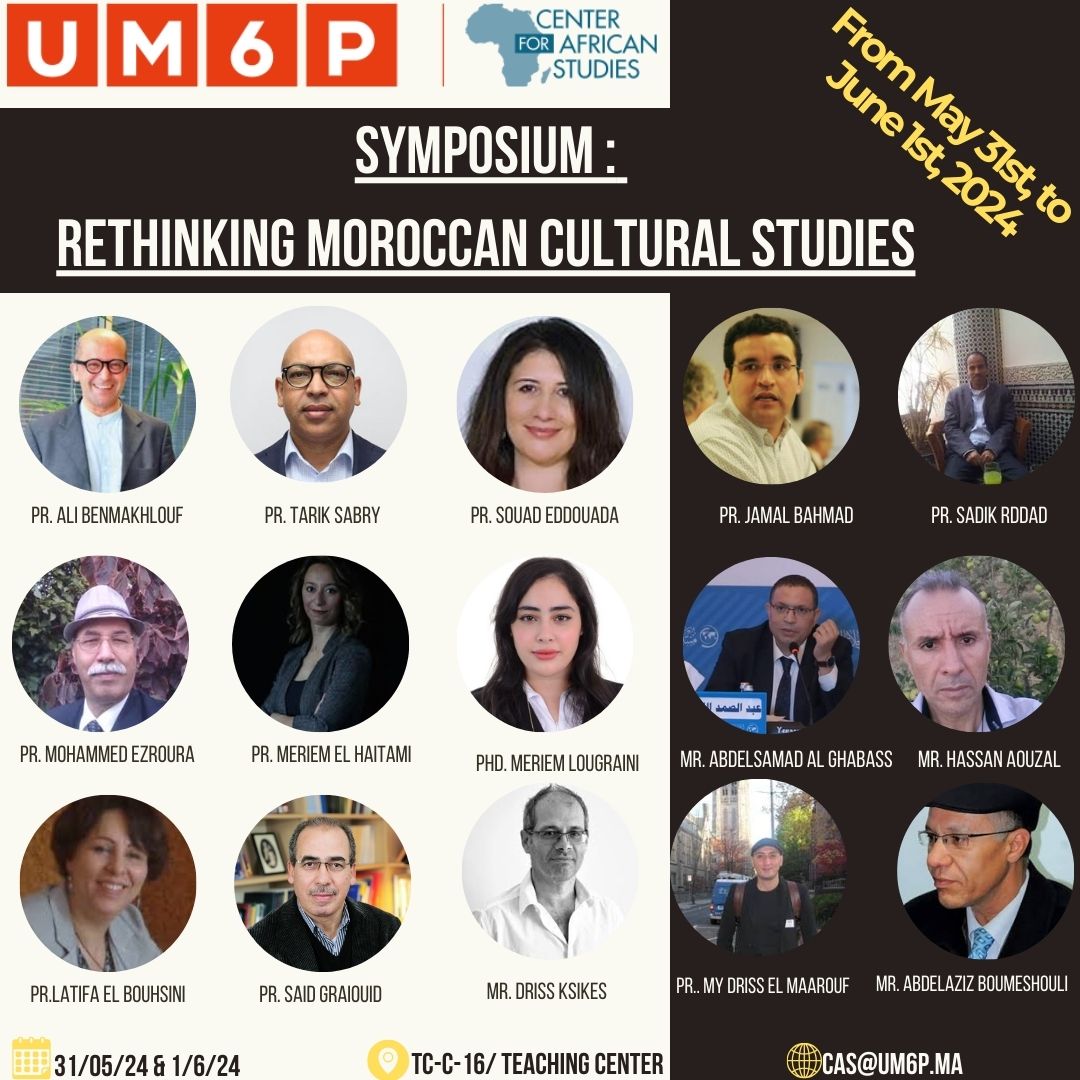

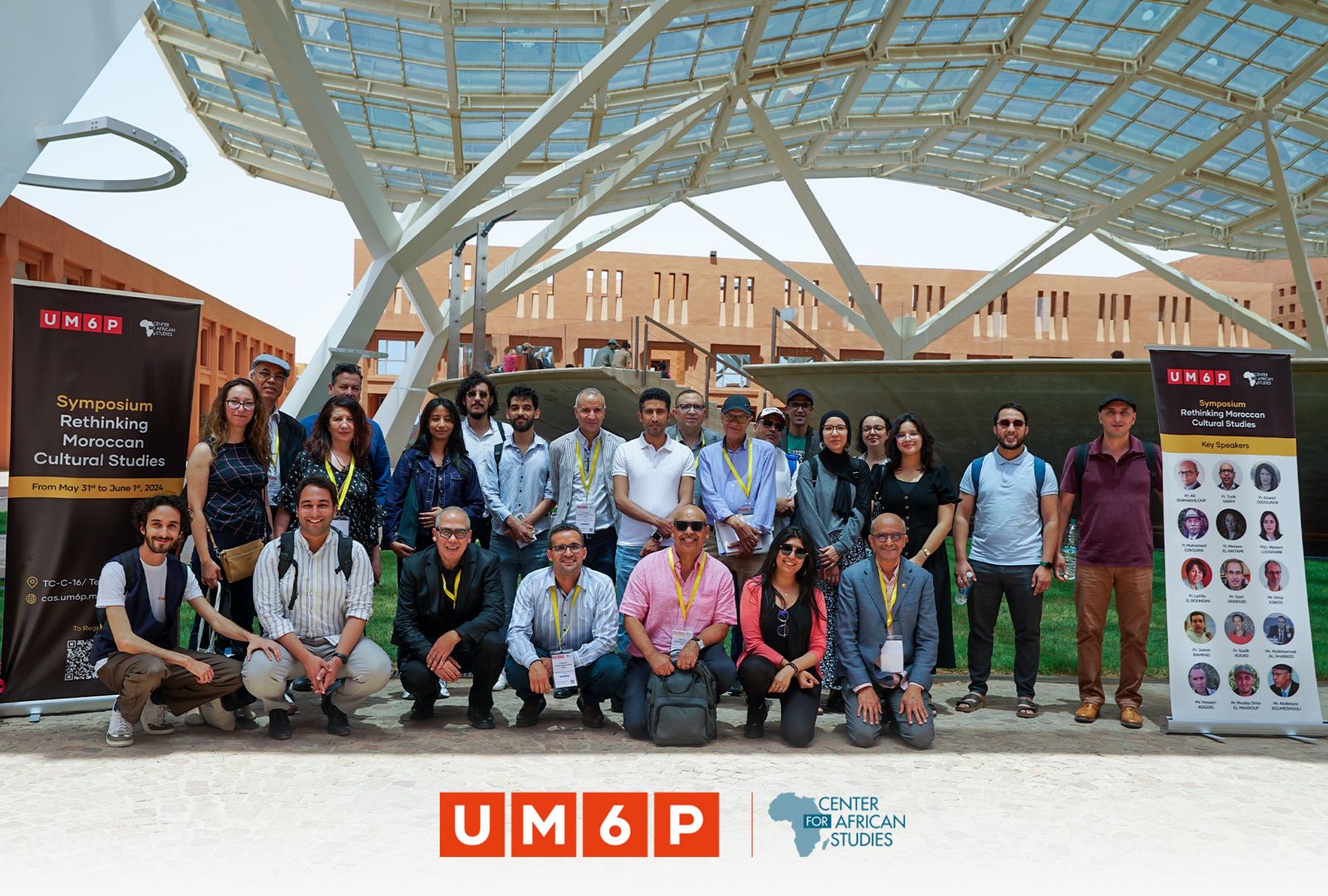

II- Symposium “‘Rethinking Moroccan Cultural Studies”

May 31- June 1, 2024

May 31, 2024

Panel 1: Moroccan Cultural Studies : Past and Present Histories

Abstracts

The Cultural Turn in Moroccan English Studies: A Break, a Bridge, or a Molehill? By Mohammed Ezroura

Any researcher contemplating the history of Moroccan English Studies (MES) since its genesis in 1964 in Rabat will be struck by a pivotal moment in this evolution. It was the moment of a shift from previously dominant pedagogic styles, syllabus contents, and the meaning attributed to EFL in Morocco. This moment was also a break with past practices and an embrace of a new philosophy of English in a foreign territory. Somewhere around early 2000, there emerged a new field of study within MES named Cultural Studies (CS). The term was first mentioned in department meetings and among colleagues, as a “cool and sexy” topic during the early 1980s when the first cohort of young Moroccan graduates returned from UK universities (London, Keele, East Anglia, and CCCS, Birmingham) and started teaching at the department. This shift, which materialized – belatedly — through the LMD reform in 2003 transformed MES from a bi-polar mode of disciplinary thinking, a binarism of Literature and Linguistics, to a triadic model of Literature/Linguistics/Cultural Studies. The latter even posed a challenge of relevancy to the traditional study of literature as an option of study.

The significance of such a change and its effects on the older teachers, the students, the type of knowledge imparted, and the philosophy of MES carries multiple significances and deserves consideration. How much of the early concerns of the CCCS was transferred to Rabat through the new arrivals from UK? Pedagogy, course contents, research concerns, attention to popular culture, critical theory concepts, politicized terminology, ideological orientations, etc… In fact, in Rabat, nobody was sure what CS meant, then, and what its pedagogy consisted of. And those who knew, kept quiet about it because of the politicized turmoil gripping the university and the society at large, and because of CS’s cohabitation with a revisionist Marxism. This paper intends to offer a genealogical reading of this “story” of Moroccan Cultural Studies since its beginning at the M5U in Rabat. With the contemporary mushrooming of CS across the Arab World — a belated arrival — after Europe, North America, Australia, Asia, Latin America, and Africa, it is only worth revisiting the circumstances of the chance genesis of CS in Rabat, particularly within the Department of English Studies. It is common knowledge now that the founders of CCCS Birmingham (Hoggart, Williams, Green and others) first belonged to the Faculty of Arts, Extra-mural and English Studies at Birmingham, but the Moroccan story is marked by a radical difference. A number of key practices at CCCS were absent from the Moroccan scene. The Moroccan students, by the time they reached the final year of the BA, would still be unable to dabble in the theoretical concepts and the linguistic competences that a native English student at the CCCS would be equipped with (culture, hegemony, ideology, masculinity, pop culture, representation, subject construction, etc.) It was only with the more draconian reform of 2000 (LMD) that cultural studies as a philosophy and a syllabi content got integrated in the system. Now departments of English could teach introduction to CS, world cultures, popular culture, film/TV studies, media studies, literary criticism, communication, etc. – showing clear inspirations by publications about British Cultural Studies – in addition to canonical literatures. These new contents were highly appreciated by the students. With the advent of the Internet and social media, the students’ options got vindicated further and turned to CS in Morocco as a de-colonial epistemological imperative.

While research and studies on gender emerged in Moroccan universities since the 1990s, the full scope of its expansion, including its pedagogical, institutional, and ideological contours, remains significantly under-explored; and while there has been a significant increase in academic research conducted by Moroccan scholars within the local context, it calls for an examination of the paradigms and modes of knowledge production that such research fosters beyond ethnocentric and foundationalist legacies, as well as pre-existing (disciplined) gender politics. This paper endeavours to scrutinize possible spaces of translatability between research and pedagogical praxis, navigating the ambivalence of educational spaces that can concurrently serve as conduits for the perpetuation of normative power structures and arenas for subversive praxes, and therefore harbour transformative potentialities that merit exploration. Central to this exploration is the critical interrogation of the praxical potential of gender studies and research through a commitment to social and political justice that subverts paradigms of power through pedagogical engagement and curricular interventions. This discussion is situated within the purview of critical pedagogical frameworks, foregrounding considerations of positional subjectivity and the valorization of pluralistic epistemologies conducive to transformative praxis.

Panel 2: Moroccan Cultural Studies and the Question of the Body

Abstracts

The exploration of “Moroccan Feminisms and the Question of the Body” delves into the intricate interplay of cultural identity, gender roles, and societal expectations within Moroccan society. Morocco’s rich cultural diversity, spanning from the Rif Mountains to the Saharan desert, shapes social interactions and deeper aspects of life, such as marriage and societal roles (Belghazi, 2006; Maddy-Weitzman, 2011). These cultural manifestations heavily influence gender roles, dictating how men and women should conduct themselves and present their bodies (Ennaji, 2014; Orlando, 2003). Traditional views on the female body, symbolizing family honor, impose significant restrictions on women’s autonomy, rooted in cultural and religious propriety (Sadiqi, 2003; Newcomb, 2009). The discourse on the female body also includes debates on modesty and identity, exemplified by the hijab, which can be both empowering and oppressive (Orlando, 2003). Feminist activism in Morocco, driven by grassroots movements, NGOs, and digital platforms, advocates for legal reforms and greater autonomy for women, challenging societal norms and promoting gender equality (Sadiqi, 2016).

تنطلق هذه المداخلة من فرضية تعرف الإنسان باعتباره كائنا لا يُناسب طبيعته، و تحاول استجلاء آثار هذه التعريف في علاقة بالتمديد التكنولوجي للوسائل التي استعملها الجسد من أجل تخزيزن الأثر و توزيعه، و كيف تشتغل كممارسة لآخر الجسد.

ضد الثقافة الإجتماعية السائدة التي خلقت هوة كبيرة بين الفلسفة و الحياة فقضت بذلك على كل إمكانية تشكُّل الفكر كنمط عيش نروم في هذا البحث التأسيس لطرح بديل كفيل بردم هذه الهوة ولأْم هذا الجرح الفظيع الذي ما فتئ يزداد يوما عن يوما و سنة بعد سنة خاصة لما حرص البعض على جعل الفلسفة محصورة على نخب بعينها و مؤسسات دون غيرها. ذلك أن الفلسفة بنظرنا طريقة في العيش قبل أن تكون رزنامة أفكار و أسلوب حياة قبل أن تعتبر ترسانة معرفية. فنحن لا نتعاطى التفلسف لكي ينعتنا الآخرون بهذا اللقب بل نتفلسف لننمي قدراتنا على العيش و لنبتكر لنا آفاقا غير معهودة في الحياة ؛على اعتبار أن المفاهيم تكاد لا تظفر بالحظوة بحسبي إلا في ارتباطها بالحياة و بالتحفيز الذي تسعفنا عليه للعيش على نحو جميل. هكذا إذن رحنا نتساءل عن الفلسفات التي تقرّبنا من الحياة و نظيراتها التي تبعِدنا عنها؛ لنخلص إلى وجود طريقتان اثنتان على الأقل للتفلسف :الأولى على نحو”شوبنهاور” و “كيرجور” المهووس بمشاغل العيش بكل ما تنطوي عليه الكلمة من معنى ،مقترحا أساليب ممكنة أمام كل من يرنو إلى السمو بنفسه بينما الثانية فهي على نهج “هيجل” الفيلسوف الموظف الحائر من أمره و المنشغل بالتماسك العقلاني لصرحه الفكري الديالكتيكي أكثر منه بالمفعول الذي تباشره الأفكار في المعيش. في هذا الإطار العام إذن كان لازما علينا أن نعرِّج بلورة لتصورنا الخاص في هذا الباب و الذي وضعنا له ثلاث مداخل رئيسية نسوقها كالتالي : أوّلها بناء ما دعوناه بالحيّز الأنطولوجي (أنظر كتابنا بعنوان منطق الفكر و منطق الرغبة الصادر عام 2013 عن دار افريقيا الشرق) ثانيها التعامل مع الجسد كرهان للمتعة و ثالثها توظيف الزمان توظيفا متعويا.

Panel 3: Gender Politics and Moroccan Cultural Studies

Abstracts

Gender studies programs in Morocco found their way into Moroccan universities within the context of the nation’s post-2004 family code reform debates in Morocco. Born and fostered within the circle of women’s rights NGO that emerged in Morocco in the mid 1980s (El Sadda 2023), the discipline of gender studies coalesced in the context of the internationalization and NGOization of women’s rights (Jad 2003) and thus positioned itself as a counternarrative to both local patriarchal structures and the bottom up Islamicization of society encouraged by the rise of a political Islam at once global and local. Gender became the prescribed term for bilateral, global-local cooperation programs, and international gender experts, local feminist activists, and governmental officials began working together to lead workshops, conferences and projects in order to teach, transform and “modernize” an obviously male-centered culture and society. This paper attempts to move beyond the frameworks and terminology that have so far structured scholarship on this topic and calls for a critical examination of networks, technical instruments and various usages, reinventions, and subversions of the term of gender. Rather than assuming that the term or conception of gender applies broadly across context and geography, this paper raises questions about the untranslatability of an odd and abstract term: Does the Moroccan context allow for an embrace of gender? Has gender been summoned or encouraged into this context? Is it translatable? What forms does resistance to gender take? What are some of the issues of translation and reordering that gender raises? Is gender yet another tool of empire and control? Why do we need to teach gender studies in today’s Moroccan universities? How could a Moroccan gender studies produce research, theory and knowledge beyond the established, Eurocentric regimes of truth that maintain the power relations between the global South—as the periphery and provider of raw data—and the global North, as the centre of theory?

Panel 4: Popular Culture, Resistance and the Political Economy of the Creative Industries

Abstracts

The experience of Nass El-Ghiwane constitutes a “contrapuntal” (Said 1994) moment in the history of music production and reception in post-independence Morocco. While Nass El-Ghiwane are today celebrated as the “epistemic heroes” (Medina 2012) of the “Years of Lead” and the “other-archive” of a historical era of social and political contestation, the band evolved in a complex political and cultural field and interacted with hegemonic forces during the first decades of their career. Besides the coercive systems of the state which sought to contain the band’s influence through co-optation and intimidation tactics, the conservative music establishment downplayed the importance of the movement, and the political left took time to recognize Nass El-Ghiwane as an active agent in the political struggle for social justice and equity. This paper argues that the Ghiwane movement created a “conscious epistemic space” (Sabry 2012, 18) which set the conditions for the transformation of the field of Moroccan cultural studies. I contend that the legitimation of the Ghiwani text as a historical enunciation of class struggle, economic injustices, and people’s desire for freedom, was an epiphany moment that spurred an epistemic turn which features popular culture (الثقافة الشعبية) as an exemplar field deserving serious academic scholarship. As illustrated by Al-Muharir (المُحَرِّر), the mouthpiece of the Socialist Union of Popular Forces, and Al-Alam (العَلـــم), “tongue of the Istiqlal (Independence) party,” media framing of Nass El-Ghiwane shows how in the first decade of its existence, the movement was either ignored or denigrated by both Marxist cultural theorists and the bourgeois urban elite for its presumed inability to articulate the dialectic of class struggle or subversion of the refined aesthetics of tarab (enchantment), a key aspect of modern Arab music. At the same time, however, Nass El-Ghiwane and their musical style transformed the collective imaginary and reshaped the ways in which people related to their past and envisioned the future. I use the imaginary to refer both to the cultural and political symbolic and material forms which create “the possibility of dreaming up another world, expressing it, imagining it, and changing the one [people] live in.” (Nissaboury 2022; 1976; in El Guabli and Alalou 2022, 63) The imaginary is also the “collective structure that organizes the imagination and the symbolism of the political” (Browne and Dhiel 2019, 394) and mediates the articulation of “something stifled and almost lost” and “does not manage to reach the speaking word.” (Khatibi 2019, 26) The music of Nass El-Ghiwane creates liminal moments of political expression, labsat (playfulness), and fourja (spectacle) in which entertainment, spirituality, and politics are intertwined. By “delinking” (Mignolo 2007) from the dominant Western and Oriental rhythms and tempos, Nass El-Ghiwane summon “veiled roots” and “indicate a different pathway” (Khatibi 1983, 213) that reinstates epistemic justice to Morocco’s music production and translates the abstract notion of resistance consciousness into rhythmic and bodily reality. As stated by Tayeb Saddiki, a leading playwright and decolonial artist, the Ghiwani movement which stems from people’s cultural history “has slowed down” the influence of “foreign expressive movements.” (Saddiki 2022; 1976; in El Guabli and Alalou 2022, 149) In the final section of the paper, I engage with the embodiment of “resistant imagination” (Medina 2012) in a sample of contemporary pop culture texts inspired by the Ghiwane movement and reflect on possible ramifications of this trend on the field of Moroccan cultural studies.

Nabil Ayouch is Morocco’s most popular filmmaker both at home and abroad. He is also the most controversial. In Morocco, he disturbs more than one party with his choice of topics and the daring tone and worldview of his films. Much has been said and made of his choice of taboo topics for his films (Gugler 2007; Bahmad 2013; Higbee, Martin and Bahmad, 2020). This paper seeks to make a new intervention in the scholarship around Ayouch by arguing that his cinema has been enabled and spurred by certain cultural policies of the Moroccan state since the turn of the new millennium. At the centre of his films, for example, is a questioning of the consensus around the definition of Moroccan national identity as Arab and Muslim to the determinant of the Amazigh ethnic majority and Jewish minority, who have seen their history, culture and, for the Amazigh, language, denied and still being largely and systematically denied. In this pursuit, his films concur and question the state’s cultural policy. In this paper, Ayouch’s films will be read against the background of a country where cultural policy assumed greater prominence in the transition from one century and reign to another, all against in a world where strategic alliances are shifting. The cultural politics of Ayouch’s cinema, it will be argued, is also rooted in Moroccan society and cinema’s transformation in response to global flows. A key flow here is the impact of international film festivals and the political economy of co-production.

Having led a series of empirical surveys and fieldwork on the economies of cultural and creative sectors in Morocco, I have been faced with a series of paradoxes that led me to realize a central problem: while named “industrial”, the cultural and creative economies in Morocco seem to have more and more “political” stakes. The related marketplace is still very limited and the political instrumentalization of creative sectors still prevalent at various levels. Domestically, cultural, and creative activities are highly dependent on public subsidies, with varying degrees of sensitivity and manifestations of (self)censorship. While economically creative projects are in 90% of cases based on self-entrepreneurship and small businesses, opportunities for visibility depend on interpersonal if not clientelist relations and proximity with authorities and sponsors. From a media perspective, the politics of popularizing art contents has slightly shifted since social media platforms have given voice to un-politically correct artists, but this has been of marginal effect on the overall monopolistic position of television politics in Morocco in relation to the creative industries. In relation to the external world, the growing need of soft power leads to a variety of instrumental tactics in the Moroccan arts sectors that range from cultural diplomacy to the design of oriented contents, while a small minority of valuable and daring actors managed to rise in the international scene, thanks to private and parallel networks. In fact, emerging dynamics are driven by international and regional funds (EU programs, French and German cooperation, AFAC, Al Mawred), but their impact is still marginal because of circulation shortages and lack of independent animated venues. By tackling these paradoxical realms, this article aims to re-question the category of ‘cultural’ and ‘creative industries’ from a critical perspective, and address the given framework, as previously designed by international organizations, and formally adopted by the government, to reveal its multi-layered, hybrid realities.

June 1, 2024

Panel 5: Culture, Philosophy and the Digital

Abstracts

This article departs from Mignolo’s (2009) provocative narrative of “coming from” to scrutinize the geo-political tensions inherent in conducting Cultural Studies within or about Morocco as a (non)Moroccan. We read the rootedness of knowledge (produced in/on Morocco) in light of what Santiago Castro-Gómez terms a “zero-point hubris” (2021), a perspective Grosfogel characterizes as “the point of view that represents itself as being without a point of view (2007, p.214)”. We argue that the idea of the zero point neglects the complexities of b/order dynamics in play in the process of knowledge production and dissemination. Order: we take cue from Frantz Fanon’s assertion that “black men want to prove to white men, at all costs, the richness of their thought, the equal value of their intellect” (1967, p.3), to confront the tensions arising from the implicit recognition that our knowledges are not equal. Border: We argue that CS in Morocco bears the dual responsibility of 1) generating “new knowledge” about Moroccan society while simultaneously 2) not “coming”, akin to ordinary Moroccans, with inherent border issues. This allows for an introspective revision of the fundamental universalism (universal nature) of the university and its implications, specifically as a site of thinking. We use the concept of thinking to explore two traditional prerequisites: “thinking time” (contemplative time) and “happening time” (active time). We assert that the conventional assumption that events require time to unfold, and thinkers need time to contemplate has been problematized by the contemporary logic of speed in the digital turn, placing CS scholars in a perpetual state of catching up with “an accelerating everydayness.” This marks a new knowledge order with implications for the traditional inquiries posed by CS and the constellation of themes it encompasses.

تجيب هذه الورقة على المهمة التي يمكن أن تلعبها الفلسفة، كتفكير نقدي، في الدراسات الثقافية، بحيث قد يشكل التفكير الفلسفي رهانا للدراسات الثقافية في إعادة التفكير في مفهوم الثقافة من جهة أولى وفي الممارسات الثقافية من جهة ثانية، وفي فهم التحولات الثقافية العميقة والجذرية الناتجة عن ولوج البشرية للعالم الرقمي، خاصة فيما يتعلق بالتحول المتعلق بوسائط التواصل الاجتماعي، من جهة ثالثة.

لا شك أن الفلسفة تشكل خلفية مفاهيمية للدراسات الثقافية، وهذا مهم جدا، ولذلك فاستعادة الفلسفة تظل رهانا من أجل إعادة التفكير في الممارسات الثقافية وأشكال حضور الجسد في هذا العالم.

This paper rehearses one key question: how can we make sense of our cultural history and present cultural tense in ways that can aid us grasp our culture (with its different components and variations) as a coherent subject of systematic and scientific enquiry? By scientific, I mean engaging with the subject of Moroccan culture(s) within the Moroccan humanities by moving away from normative discourses of culture to delineate a coherent, critical and scientific project requiring the conduct of systematic and original empirical research into both our past and present cultural tenses. I argue that it is within the epistemic manoeuvring processes of re-territorialisation (reconnecting the study of Moroccan culture with Moroccan philosophy and thought) and de-territorialisation (de-essentializing and reconnecting our study of Moroccan culture within universal thought/other-thought) and the mechanising of ‘otherness’ as a form of ethics, that creativity within the study of Moroccan culture(s) can take root. With this kind of manoeuvre, I contend, we are guaranteed flight or escape from all sorts of ontological imperialisms as well as from the many intoxicated metaphysics of authenticity. Taking my cue from Khatibi, this paper also proposes another double movement. What I have in mind is a dialectical phenomenological exercise that lends its attention to: a) how Moroccan scholars (as producers of knowledge) ontologically experience being part of a new field, such as Moroccan cultural studies, and b) how both the use and interruption of phenomenology, as a philosophical and methodological approach, can help us to expand the plane of Moroccan cultural studies.

Watch Full Symposium

III- Symposium “Actualité’ of African Philosophy”

January 15-18, 2024

January 15-18, 2024

Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, Sciences Po Paris

A symposium was held from January 15 to 18, 2024 at Toulouse Jean Jaurès University and Sciences Po Paris. The theme was “L’actualité de la philosophie africaine”.

This symposium proposes to present works in African philosophy currently being carried out in France and internationally, particularly in Africa. It aims to contribute to : demonstrating the need to refer to the works of African philosophy in our own time, and their relevance to the most pressing social and political issues, in Africa and the rest of the world; integrating the field of African philosophy, across its geographical and linguistic differences, while at the same time opening it up on an inter-area and inter-disciplinary level; to take stock of the structuring issues of its contemporary history (the definition of African philosophy, the liberation struggles, the problem of ethnophilosophy, the articulation between the continent and the diaspora, between the north and the south of the Sahara, the globality of African history and situation, providing a criticism of the traditional history of philosophy, etc.). In so doing, it also aims to help introduce the academic field to African philosophy, which is still largely ignored in France, and to this end is anchored in local institutional initiatives: at Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, the creation in 2021 of an African Philosophy Teaching Unit in the Master’s program, the organization of the Rencontres des Études Africaines en France in 2022, followed by the creation of the Structure Collaborative de Recherche en Études Africaines led by the seminar “Les Afriques au pluriel”; at Sciences Po Paris, the creation of the “Africa” minor in the undergraduate program and the foundation of the “Africa” program.