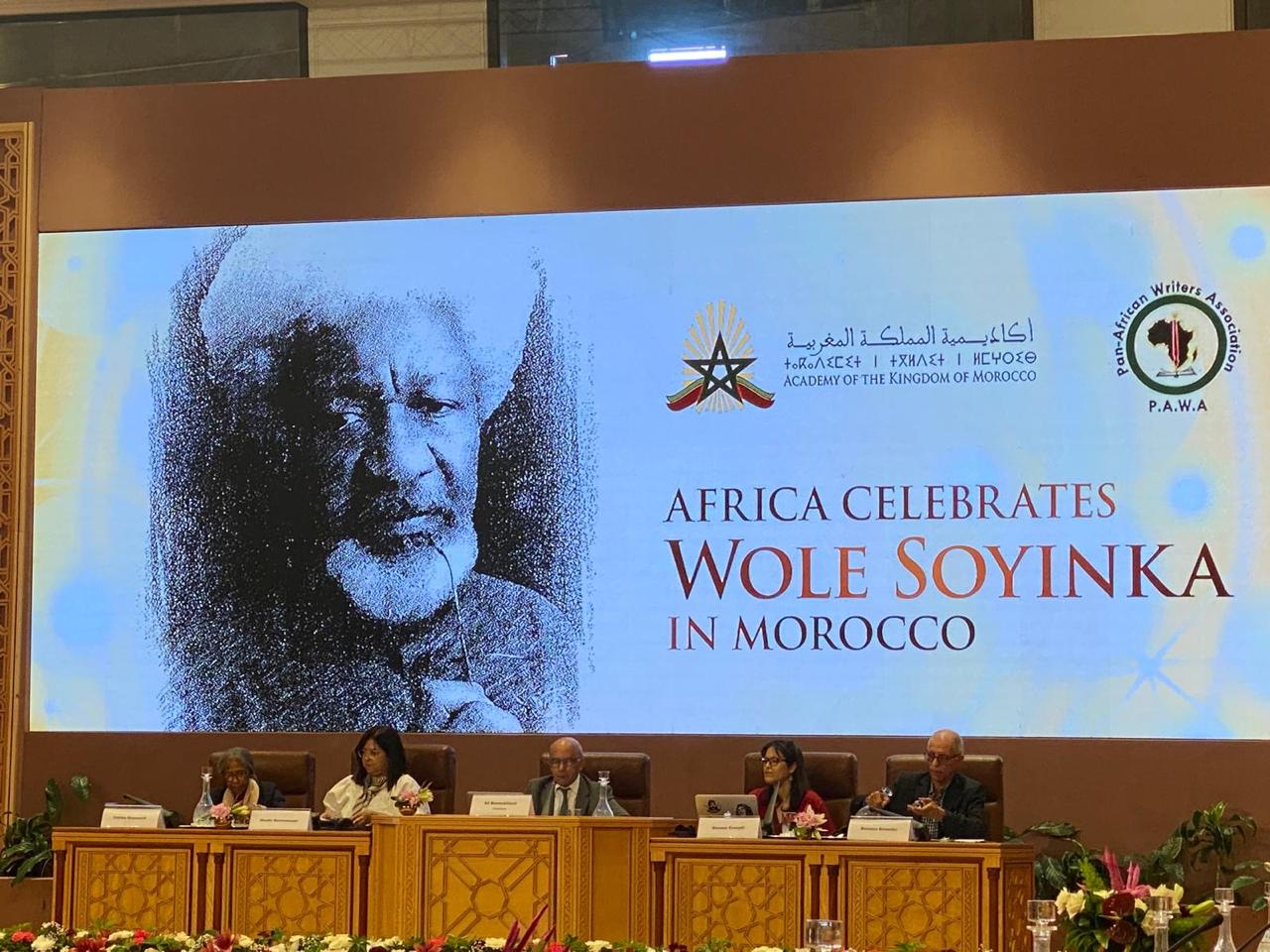

Africa celebrates Wole Soyinka in Morocco

Pr. Ali Benmakhlouf

Wole Soyinka, the voice of resistance

Introduction to the panel by Ali Benmakhlouf, member of the Academy of the Kingdom of Morocco

Academy of the Kingdom of Morocco on July 9th, 2024

Pr. Ali Benmakhlouf : Wole Soyinka, the voice of resistance

Wole Soyinka, is always asking this question: What, where is our part of humanity? Certainly not with the fallacy of nationalism. To this question: what is our part of humanity? His response is very simple and very strong: the human community has to be run by a constant and uncompromising criticism of oppression, corruption, inequality and misrule wherever they occur. He shows the road to freedom, the road that was Mandela’s path, which still has to be ours if we claim to have a part of humanity. His fame as a public personality is made of his uncompromising fights for human rights, as well as of his literary work.

Let’s quote The humanist saying in his native Yoruba language: “Ori kan nuun ni/Iyato kan nuun ni », which we can translate as : “That is one person/That is one difference”. Differences are always individual. Exclusions are collective as, unfortunately, racism shows us every day.

Wole Soyinka prefers the words “interaction” and “hybridity” to the word “influence”, because, as he used to say, we never know completely what the influences that we are dealing with are, but we know how interactions allow us to recognize our own culture in another one. Interactions, references, rather than influences. We may say that his work is a school of withness, relatedness, connectiveness, a school that sets all cultures in interaction, each one witnessing the other.

Wole Soyinka is always sensitive to the articulation between art and politics. In the lecture given in Sweden in 1986, he went on explaining what resistance means. At that time, South Africa was still under the Apartheid regime and the main part of his speech was about that country, he was claiming for the end of their racist government. The past is claiming for its presence, “enacting its presence”.

Literature and life are intricately woven in the very structure of his writings, of his life, the life of African people. He said that he accepted the Nobel prize “as a tribute to the heritage of African literature, which is very little known in the West. He regards it as a statement of respect and acknowledgment of the long years and centuries of denigration and ignorance of the heritage”, a heritage which he and other African writers have been trying to build: Leopold Sedar Senghor, Chinua Achebe, Ousmane Sembene, Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Bessie Head.

Literature, with its thick descriptions, sheds light on the complexity of human choice and different levels of reality in The lion and the jewel. It sheds light on the different levels of power in Opera Wonyosi, without ever supporting any kind of theory:

He rejects the fallacy of misplaced struggle and pay attention to history, to the dreadful affinity between new independent governments and colonialists.

Let’s say few words about Theatre. Theatre, unlike other fields of literature, gives its audience not only words to listen to, but also images, songs, different idioms, actions. So the stage is a “social vehicle” and theatre is “a tactile process” that impact most people quite easily. You, yourself feel alive when your printed words are brought out on stage.

His theatre claimed for justice in the open spaces. He was creating a public space with his plays: he was not just creating plays in a public space.

he is also a lecturer all over the world and a poet as well : Poems from Prison (1969), Mandela’s Earth and Other Poems (1988). You also produced a critical work which always has a close relationship with your imaginative work, mainly in your book entitled Myth, Literature, and the African World (1976), and you revealed in a decisive manner how philosophers who we cite for their commitment to enlightenment, such as Hume, Locke, and Hegel, have an obscure side as “theorists of racial superiority and denigrators of the African history and being”.

Soyinka was in jail, thrown in solitary confinement, he were in exile in Ghana, but he was still standing. His writings have become his way of making resistance a continuing process, even if he knows that literature doesn’t always suffice to correct social and political ills.

Through an African’s eye and mind, Wole Soyinka describes more than the African life. He describes and encourages the sources of self-regard in all human beings. “Chronicles of the happiest people on earth” was a novel he wrote for meeting an “internal demand”: he wanted to expunge something that was coming to a collective boil, that is to say to tell the truth in a harsh way about the Nigerian society, about all the wrongs done to people, about all these people separated from others because of their rich position, and thinking they can be okay with that. We understand that the title of his novel is quite ironical: it has not to be taken at his face value – “happiest people on the earth” – but it sounds like a phrase he heard in one context, and spoken in another context.

Everyone recognizes wole soyinka’s genius for satirical phrase-making. In his play called “Opera Wonyosi”, staged in December 1977, he describes with such a sense of humor, and in such a satirical style, how dictators (at that time Bokassa and Amin Dada) did wrong to their people and how they were supported by those who are guided by greed, the venality of ruling circles. The two languages, English and Yoruba, are entangled in the title, Opera Wonyosi, and the second word in Yoruba refers to a kind of very expensive fabric worn by the rich who wanted to show off in the 1970-1980 decade

In the speech he gave in Stockholm, his words were events, and as events did contribute to that major political event ( i.e. the end of Apartheid) , because his words do not have only a meaning; they have also a weight, a weight of resistance and they were pronounced by a voice of resistance.